The wind blows across the prairie like a saw, cutting away the dead wood and turning everything into a sculpture. Nobody’s there to see it but the rats and the snakes and the grasshoppers. Two men lie next to each other, both dead, both wearing identical outfits—cheap suits, bowler hats. The wind hasn’t had time to work on them yet so it’s up to the flies crawling over their coats and hats and leather boots. And flesh, of course.

The flies don’t seem to be having much luck.

They were train robbers, Poindexter and Guillaume. The world was a richer place then: easier to steal. The treasure wasn’t gold or silver but banknotes, but they still made a pretty good penny off robbing trains. They had got to the point where they hoarded the money like dragons hoarded gold anyhow, kept most of it in a series of underground caves.

To see them together you would have thought Poindexter was a businessman. Suit, bowler hat, tidy mustache. He had a kind of northeast feel to him but it was hard to say where from. Not New York, not Boston. Somewhere north of the Virginias. He was thick. So broad through the torso you would have been justified in calling him fat but that wasn’t the important part. The important part was that he was strong as an ox and contained within himself reserves of both cleverness and cruelty. If you saw him apart from Guillaume, you’d think he looked like a thug. He wasn’t from New England but from Manchester. He carried with him at all times a butterknife that had been carved into a very small saw. It was rusty and dull, couldn’t hold an edge, and was stained with old blood in the crack between the handle and the blade. Other knives came and went but this one was with him always. Sometimes he whispered to it in his sleep.

Guillaume was—had been—one of the last of the old kind of fur trappers in Canada. Lived in the north wilds of Quebec. Fished through holes in the ice covered with skin tents. Eyes red from living with so much smoke. Smoked meat, cleaned furs, avoided his fellow man. Even now he wore a yellow leather jacket with a fringe of leather along the sleeves, kept his gray-and-white hair long and straggly, wore an eye patch. Stank of grease and smoke. Wore tied leather boots lined with rabbit fur. Had mice skulls in his pockets, which he would give to small children when bothered. He was enormous. Had been mistaken for a bear when he was younger and his hair was black.

The story was, he’d killed a whore who’d looked under the patch while he was passed out drunk. Somehow he’d known.

From our point of view, they were two men living in rougher, wilder times. From their point of view, they were watching the old ways die out and didn’t much care for it. The trains came and went, carrying their burdens of men, men, always more men. Their women and children, too, respectable ladies who wanted social halls and churches and schools. The prairie echoed with the sound of hammers driving nails into pine boards. The wild men were dying out, and Poindexter and Guillaume didn’t like the notion of it. So stealing from the trains wasn’t just a pastime or a means of making a living. Neither one of them had need of money, as such. They hadn’t been the kind of men who’d made money an equivalent to worth. No, the reason they stole money from trains was to announce to the world: put your trust in this stuff and see what it gets you. It goes up in smoke.

The problem was that the money had started getting hold of them. They had started out destroying the stuff, blowing up the trains, killing every man, woman, and child among them, driving off the cattle, prying open crates, hacking open flour sacks, pissing on clothes, and burning the money in a great whooping bonfire that drove the natives away for fear it would take the prairie and spread, which sometimes it did. But time had worn on, and the fires had grown smaller, then disappeared, and now they were at the point of carting the money away with them to their cave in Kansas.

But recently it had got even worse.

Here’s what it had come to: Guillaume, being perhaps the more human of the pair, had taken a woman captive and had her on the saddle in front of him. Her hands were tied in front of her with rawhide. He’d soaked it and now it was drying out, getting tighter. The woman’s hands were swollen and red but turning purple. Soon they’d be blue. She’d thrown herself off the horse a couple of times. Her face was beaten and bloody, just the way he liked it. She had a rag stuffed in her mouth.

Poindexter didn’t like it. Oh, he liked hurting women as much as anybody, and he understood the need for a snack. It was the rag he didn’t like. It wasn’t torn off something. It wasn’t robbed from one of the corpses, not even the woman’s husband or little girl, lying dead on the scrub grass with the grasshoppers zinging through the air around them. It was a rag that Guillaume had brought with him, took out of his fringed leather coat, close to his chest. It spoke of a premeditated act. Of a plan.

“We’ll kill her at the top of that ridge.”

“We’ll kill her when I say so.” Guillaume stroked the woman’s hair. It was matted with blood and dirt. Gold underneath, but there was no getting around that. “I took her, I kill her. You want a pussy puss of your own, you take one yourself.”

“We’ll kill her at the top of that ridge, I say. I don’t want her polluting the place with her filth.”

“I’m going to lay her down on top of the money when I do it. Nice and slow. I like to listen to them singing.”

The woman had had the horror beaten out of her, including most of her sense. And if she understood a word of what they were saying she couldn’t say so, what with the rag stuffed in her mouth. At the moment, she was trying to swallow without getting the tail end of the rag, which tasted like rotten cheese, drawn down into her stomach.

They were monsters, Poindexter and Guillaume, no doubt about it. Let’s not mince words here. They were murderers and monsters and train robbers. Let’s not heroize them. I can understand the temptation to do so. We call some men heroes that aren’t. Dig deep enough through the skin of anybody, you’ll find something that’s better left unseen, we know that. That’s why we like our villains so much. They’re closer to the truth. They show us what we already know: that, given the opportunity, we’ll take every virtue and piss it away for gain. Sure, sure, the hero kills the villain but that’s in stories, right? We know who the real hero is. It’s all there to see.

But Poindexter and Guillaume are not those kinds of villains. They resist the snuffing out of humanity but that doesn’t make them any better than monsters. It doesn’t make them saints. It makes them monsters who like a particular spice of individualism to their meat.

Keep that in mind.

The train. It was stiflingly hot in the summer and rattletrap-cold in winter. The beds swayed at night and every creak, rattle, and snore could be heard through the curtains, and she didn’t dare move lest she fall out of bed. She never slept, just laid awake and stared until she couldn’t tell what was a dream and what was real. She dreamed of the dead, come back to haunt her. The only time they could find her was when she rode the rails, the unending thrum of the iron under them, the vibrations of the carriage, the smells of too many people shut up together for too long.

Karen was traveling with her family, that was, her husband and surviving child, back to Kansas. She’d lost a pair of twin boys born too small about six months ago. Since then she hadn’t caught and was glad of it. Even though she wasn’t popping them out the way “pioneer” women were expected to. The attitude in Kansas seemed to be that there was a continent to fill, and if she didn’t help fill it, then that would mean there was more room for men from back East, the constantly flowing river of bodies that spread out from civilization like a plague. But after she’d lost the boys George hadn’t touched her. It wasn’t his way to weep but she felt the weight of the boys’ loss in him, too.

She’d gone back to Massachusetts to stay with her mother while she recovered. Mattie played with Grandma while Karen wept, and huddled inside a wrapper of blankets, and drank cold tea and broth from trays, discreetly appearing and disappearing while life went on outside the narrow door to her childhood room. She wrote letters to George and prayed he hadn’t done himself a mischief while she was gone. Now he’d come back East on business and it was time for her and Mattie to come home. His face was long and turned down at the mouth. It was a relief not to have to pretend to happiness with him.

Her stomach churned with every bump and lurch of the train. If she’d had to have ridden out here on a wagon train she would have killed herself after a week. As it was she clutched her hands together in her pearl-gray gloves, which seemed to show up dirt and stains even more than whites ones did. She hated trains. She hated this train. She hated the springs under the cotton batting, which was never thick enough. She hated the smell of ground-in dirt and rust underneath the powders and perfumes the women drenched themselves in. She hated the way she’d given Mattie opium to make her sleep, and she hated the way her child was so full of livelihood when she was awake. She hated the other passengers. They felt like fleas crawling through her clothes. Their eyes were on her always. If one person wasn’t staring than another one was. She hated the sky, its unwearied blue that turned to contemplative black at night, so wide and yet so filled with stars. She wished for life in the city, with its heavy smells and gray skies and hopelessness. On the prairie one was constantly surrounded by people who told one to keep one’s chin up, to always look on the bright side, etc., etc. She stared out the window and hoped that no-one would speak to her.

She didn’t want to move forward. She didn’t want to move on with her life. She didn’t want to get back into the old routines. She didn’t want to keep the books at the store. She didn’t want to sweep out the dust or rub dishes dry.

She didn’t want to deal with the business of living anymore. If only it hadn’t been for Mattie she would have found release.

She was sure George felt the same.

The train rumbled. It was that time after sunset in which the world became haunted. The barren landscape flickered by. Stunted trees shadowed the course of a stream. They appeared in clumps, like the dots and dashes of a telegraph message. The grass turned gray, the sky leaden.

Her eyelids sank. She would sleep. She would sleep in the seat next to Mattie, and not in the bed. She would never sleep in the upper berth again. Her daughter was a warm presence beside her, curled up like a cat with her feet tucked under her blue wool coat. George sat opposite to her, studying her face. His mustache had grown longer, covering both lips and part of his chin. He looked as though he wanted to ask impossible questions. She closed her eyes.

The train jerked, and then she was flying.

The horses had been damaged. If they hadn’t been damaged, they would have gone mad. But Guillaume knew the trick of it; he had a drill-tipped metal rod that he kept in his pack for just such an event. He was very matter-of-fact about it, not horrified in the least. He thought no more of a horse than you might think of a machine.

The three of them, the two monsters and their passenger, rocked along with the horses. The tack jingled dully, more like a pocketful of pennies than like bells. Your mind could only stay alert for so long in those conditions: the heat of the day, building after the dry, dewless chill of the night. The sweat on your skin evaporating before it had a chance to crawl, spiderlike, down your skin. Your identity fades, slips, transforms. Who are you, you wonder, as the heat ripples off the dirt road ahead.

Poindexter was aswim with souls, thousands and thousands of them. Human souls, bison souls, souls of small mice and large, ragged-furred rats. Horses, now. The souls of horses usually escaped him. Too restless. He shifted in his saddle; the smoothed, heavy cotton of his trousers squeaked against the leather. He wasn’t uncomfortable with the woman, as such. Just Guillaume’s interest in her.

Was it some perversion to do with the money? Had it been Guillaume who had made the decision—who had pushed, encouraged, manipulated—to save it, instead of destroying it? He, Poindexter, was the manipulator. He, Poindexter, knew that his function in their duo was to manipulate. He was the talker that contained the hidden threat. Guillaume was brute force that contained a direct cunning: and yet this plan, this plot of his seemed to contain manipulations. Hidden threats. Had Guillaume become Poindexter, and Poindexter, Guillaume?

When you get off a horse this kind of thinking fades; you know who you are. Guillaume knew that this mindlessness came from the properties of the body he currently inhabited, that this strange wandering of thought was not madness as much as some kind of surreality constructed over the gaps in his idle thoughts. It was like dreaming, a torturous dream inflicted by one’s own flesh. He had inflicted such dreams on others. He had used the properties of the flesh to drive men mad, and take their souls. That it was happening to him seemed an indication that he was, himself, being infiltrated. Manipulated.

Violated.

Had he, Poindexter, been damaged? Had Guillaume taken the rod, pushed his eye gently to the side, and drilled into his skull? It was not beyond the realm of possibility.

“Guillaume,” he said.

Guillaume grunted.

“Kill her or I will. Now. Before we get to the caves. This is wrong and you know it.”

Guillaume spat on the ground, turning his head so he wouldn’t foul the woman’s dress. Poindexter felt the hairs on his arms raise, even in this heat. The grass around them sniggered in long ripples across the prairie. The wind gusted over his skin and brought up gooseflesh.

“Won’t,” Guillaume said. “You had better leave it alone, my friend.”

“Tell me what you’re doing.”

“Saving for later.”

“You’ve never done that before.”

“That’s true, I haven’t. Now shut it before I knock you off that horse.”

Before, he had always been able to read Guillaume’s mind, as it were. They had been of one mind, one purpose. And now they were not. Who had decided to keep all the money? Had it been him? He couldn’t remember. There was a stone in the caves of his mind. The intricate caves. And in order to remember he would have to roll back the stone.

And then no amount of damage would stop the horses from bolting.

The train screamed. It was a nightmare of sound, pain, and disorientation. Karen flew through the air like a doll, bouncing off the seat backs, the roof, other passengers. Her world mercifully turned to blackness. Her daughter died, shall we say, instantly. At any rate she never woke from her opium-induced slumber. Karen’s husband, George, had the grief of remaining conscious, pinned to his seat with a wooden pole from the underside of a folded-up upper berth, meant to help the passengers steady themselves as they walked. His guts had been punctured, a nice slow death as far as Poindexter was concerned. George tried to pull the pole out of his flesh but he lacked the moral strength to do so. He tried not to despair; every quiver in his guts was like a knife. He wished for one last sight of his daughter or wife, although such a thing would have hurt him worse than he could have imagined. He was a good man.

The night flowed in around the train car. When the train finally fell silent but for the sobbing and fear, the only sounds were of Guillaume and Poindexter, having tied their horses at a nearby farmhouse in preparation for their adventures. They passed from car to car, feeding.

They supped on the rich; they feasted on the poor.

There was no money on this train, not as such—only what the individual passengers carried, which was hardly worth the time it took to paw through their pockets. They bypassed pocket watches, jewelry, false teeth, ivory canes, etc. In times of scarcity they would have considered taking a silver-framed locket containing the very picture of love lost, or a child’s toy sans child, or any other object infused with the essence of a poignant memory. They would have hoarded.

They would have taken some for later.

But this was not a time of scarcity—was it? They were fully fleshed; they ate well; the world was what it was; the men from the East flowed, they oozed, they squelched. There was plenty, even if there were others of their kind mucking about, to go around.

Poindexter sipped Mattie’s last heartbeats, then pressed his lips to Karen’s. She was lovely, as bruised as an apple, and mercifully unaware of him. One brush against her lips—one taste of the pain awaiting her—and he laid her carefully outside the train car, to await her wakening.

Perhaps she would be well enough to walk. Or to run. They could afford to take the chance of losing her. They could even let her go. To spread the horror. To make it ripe.

Guillaume saw it, of course. He saw the tender way Poindexter, having overrun his human form, lifted her gently out of the train car and laid her on the ground. Meanwhile Guillaume chewed the twisted wreck of the engine, sucking out its soul from the metal marrows, licking its blood and steam. Poindexter had been acting oddly lately. He’d been taking all that money. Hiding it in the cave as though it were somehow useful or precious to them.

Would it lure prey to them? The humans pursued money. He hadn’t protested, because Poindexter had it in him to be clever, to see things that could and ought not be seen. He could see surprises. Guillaume took a solid pleasure out of Poindexter’s plans, because Poindexter revealed all the surprises ahead of time. To know the future made Guillaume feel godlike. Not for very long at a time. But it was nevertheless a pleasure he could not obtain on his own, not from the destruction of any number of humans, or any number of betrayals, or any number of the uses of machinery.

In his way, Guillaume was worried about Poindexter, who seemed to have split in two: the Poindexter who knew about the money, and the Poindexter who didn’t. Madness was a human occupation. He ought to kill Poindexter and free him from the flesh but who knew when he’d find his way back to Guillaume again? Or how angry he would be when he did.

No. He would have to find another way.

He looked at Poindexter, picking through the train car. When Poindexter was done Guillaume planned to pull apart the sleeping berths. Their smooth, varnished wood was sensuous on his tongue, full of hushed sex, illness, crazed nightmares, guilt.

If only he had been happier in his life, he would have avoided all this. He was not like Poindexter, he’d been born human. But he had despaired, and in his despair, opened himself to influences out in that long, lonely wilderness. He had longed to surround himself with men, with the signs and creations of men. And the hungry ones had found him there. He had opened himself further and further…now he was the kind of thing that machines despaired of, the ender of their lush mechanical essences, their nightmare.

Poindexter did not truly understand what possessed Guillaume. A predator evolves with its prey; this Guillaume had always been aware of, even in Quebec. Poindexter hunted for a different kind of prey than did Guillaume, and found him foreign. Poindexter had come from the Old World, and had Old World ways and knowledge and cleverness, for hunting men.

Guillaume had evolved with the New World, had been possessed by it. Under his coat he was metal, a man being remade as metal. Soon it would begin to cover his face, to invade even the semblance of humanity that remained to him.

And then Poindexter would go, and he would be alone.

If Poindexter wished to savor the woman, Guillaume reasoned, then she must be good prey. She contained some essence, some perfume. Within his coat he had a rag that he had carried with him for years, not out of any meaning, but because he needed a rag. When he had started becoming metal he carried it with him, he sniffed at the stink of it in order to remind himself what humanity smelled like. At first it had stunk…then it had smelled of meat…now it was cloth, nothing more. At first he had been able to resist the horror of the loss—the loss of his stink, which he would have been glad of, when he hunted beaver and elk and rabbit!—but of late it made him gnash his teeth at night, with the groan of strained metal.

He pulled out the rag, shoved it in the woman’s mouth, and threw her over his shoulder. She weighed nothing. His belly grumbled. He had held himself back, had not eaten his fill.

He would eat this woman, and take on her essence. He would take on the essence of her that was full of fear of his old, human essence. Her fear would teach him how to be human again.

He would eat her; they would burn the money; all would be right again.

Reaching the limestone cavern, a couple of hundred miles to the southeast, meant they had to keep the woman alive for days on end, a tiresome business that Guillaume had had more experience with than Poindexter. Guillaume knew how to hunt things that weren’t human, and insisted they do so: both to prevent their being followed as well as to spare the woman the distress of cannibalism. He had tried to explain this to Poindexter, whose instincts pointed toward causing distress rather than sparing it, but Poindexter only turned his head away. “You’re the one who wants to keep her alive. What does it matter what I think?” Bitter, resentful. Soon, Guillaume promised himself. Soon it would be over. But the anxiety within his increasingly metal mind sounded like a spring, twisted, its metal shrieking its deformity as it was forced into actions it had never been created for.

He could hear small pings, the ticking of a clock in his head, which was really the movement of gears and springs and ratchets. The horror was that he found the ticking soothing. In dreams he found himself contemplating entering the guts of a city, lurking below it, preying on the machines that lay below the surface, helpless, unguarded. That which possessed him was not only rebuilding his body, but his soul.

He roasted a brace of rabbits over a small fire—waste not, want not—and lurched with a residual, mad nausea every time he rose to turn the green-wood spit. Poindexter stared at the women, smacking his lips, as she watched the skinned animals over the haze of coals. Earlier, when the flames had been high, she had hummed to herself, rocking back and forth with her arms around her knees. A lullaby.

She watched the rabbits roasting because she was hungry, although their glistening bodies looked suspiciously like cats, their ears having been removed by Guillaume when he skinned them, apparently using the back edge of his right pinkie, as though it were a knife.

She’d watched the flames because something had whispered to her, out of the flames. Not to her, as such. But whispering. A cacophony of whispers, as though she were at a theater where the curtain had been down too long. She could not understand the words, but she felt the emotions of the whisperers. The emotion was longing—dissatisfaction. A sense of restlessness. A sense that if only one tried a little harder, worked a little more loyally, one would find it. Whatever it was. Not family, not friends. It could not be found in drink, although drink could suppress the need to find it for a while, as could—she noted curiously, for she had never really enjoyed it—sex. Food could comfort those without it, and…

…Karen stared into the flames and tried to remember when she had first heard the whispering. Before the train wreck, or after? She could not sort it out, but she suspected, by the time the flames had died down, that she had been one of the whisperers, back East.

At the time her despair and longing for death had felt to be much more than dissatisfaction. Her sons had died, and there was nothing to be done for it. The other lives around her had had no meaning. A well of resilience within her had been drained, profoundly and permanently drained—or so she’d thought.

But, looking into the fire, and sensing the wash of dissatisfaction coming through the fire, she felt as though a small trickle of hope were coming back into her: a small spring in the pit of her despair.

It hurt.

Which was, after months of numb, deadening despair, an unfamiliar sensation.

The landscape changed around them, from the open, gray-dry prairie, to the rising crests of the Ozarks. The world was greener, a little less abandoned, although not exactly populated. Through the heavy trees they could glimpse a disarrangement of the natural order: farms cut out of woodlands, thin trails of smoke, a dog barking, a double-line of dirt through a meadow. Nothing like Kansas City or the thick polluting scabs of civilization out East. Still, these small things reminded both Poindexter and Guillaume that a world was coming to an end. Wilderness was dying. The idea of wilderness was dying, here, as they watched.

Nevertheless the things they carried inside themselves were able to warp the world a little in their favor. They remained unseen.

To Karen, the whispering was becoming louder, almost deafening. She shivered constantly.

“Is it sick?” Poindexter asked. “Dying? We could kill her—it—now, you know."

Guillaume urged his horse a little faster. At the end they were galloping up the trail to the cave, with its low, gaping, sloppy kind of mouth. Their control over the horses was starting to slip; the horses foamed at the mouth and trembled with exhaustion. Even in their mentally deadened state they seemed to feel fear.

Inside Guillaume’s head was a kind of tearing sound. He would start to think a thought, and be unable to finish it:

You are losing your—

After the woman—

Too late, it’s—

The machine is—

The horse ran blindly up the crushed-rock slope and nearly brained him on the mouth of the cave. It refused to stop when he leaned back and jerked on the reins but turned sharply, throwing the two of them off. Guillaume’s horsemanship seemed to have left him. The woman skidded across the fallen rock. He had stopped tying her hands together; she had become catatonic, unable to eat or speak, or do little more than breathe. In the end he had removed the rag and stuffed it down the fetid front of her dress, in case she choked on it. Now she lay stunned, perhaps dying.

He got his boots under him. His spurs jingled, or else it was his soul. Poindexter rode up behind him, looking down on him with the sun at his back. Guillaume could feel the sneer on Poindexter’s lips. Broken, everything was broken. He picked up the woman. On her lips was a smile, a horrid, evil smile. But there was no time to consider it.

The woman suddenly gasped, stretching out full length with her hands over her head, arching her back. Cloth ripped. He should have left her bound. She was trying to get away.

“Help me,” Guillaume said.

The woman thrashed and kicked in his arms, not frantically or consciously. Her eyes were still closed. She was a dreamer swimming to the surface. Suddenly she had flipped out of Guillaume’s arms and was on her feet. She brushed her filthy dress down. Her blond hair lay lank on her shoulders in clumps. They should have raped her. They should have killed her.

She rippled with strength. Her dress was splitting down the seams, through her lower arms and across her torso, showing a rotten yellow slip underneath, stained a garish orange, the color of illness, not of wholesome blood. She opened her eyes and they glowed blue.

Poindexter was taken back to his younger days, in a place you might call Hell, if you were particularly unimaginative about other realms than these. He had once tried to torture something stronger and nastier than he was, and had run squeaking in terror when it had burst out of the human form it had been wearing. He wanted to bow. He wanted to beg for mercy. He wanted to run.

Poindexter’s horse reared. It was a choice between trying to stay astride or rolling free. He shoved away from the horse, stumbled, then did something small, and brave, and nearly human as the woman turned toward his companion, his friend: he attacked her.

He threw himself on her back. With a flick of his wrist he had a razor out from his sleeve and open. He slashed it across the woman’s throat. Then he flew through the air, rolling down the slope, keeping his head close. He lost the razor, whose specialty was cutting through hope. The world flashed: sky…rock…trees…

He hit a boulder and stopped, then woozily got to his feet. The woman staggered into the cave. If she was bleeding he couldn’t see it. But he had distracted her from Guillaume, so it was enough.

The whispers pulled Karen forward, step by step. Although she still had no idea what was pulling her—what was happening to her—it was at the exact moment that she walked through the mouth of the cave that Guillaume calculated the truth.

He followed her, jingling and creaking. His limbs felt heavy, solid, unstoppable—but that was a lie, he knew. Rust seemed to creep through his limbs.

Guillaume entered the cave behind the woman as though hypnotized. His gait stiff and staggering, the fringe of his leather jacket swinging wildly. His friend had been captured, enslaved.

Poindexter ran up the hill and threw himself onto Guillaume’s back, trying to knock him over. Guillaume rocked forward, but regained his balance. Poindexter slid off his back. The fringe of the leather jacket swayed.

“Guillaume,” he said. “Stop.”

But Guillaume had lost his thoughts entirely. His own transformation had overtaken him.

Poindexter jogged around his friend and struck him in the face. It was a powerful punch but did nothing. Guillaume came on like a juggernaut. Poindexter looked over his shoulder: the woman was heading directly toward the cache of money.

Then he knew, too, what was happening.

“My friend, my friend,” he laughed. “You were right. I should have burnt the money. I should have burnt it. I should have made it into a holocaust.”

Guillaume’s eye patch had slipped. His eye was no longer human, but shining copper. And the eyelid under it was drooping away, showing the shining brass underneath.

It was too late. For how long had it been too late, and he had not known?

Karen found the false wall along the side of the cave and stepped through it. It led down a crevice, a thing not made by human hands but marked by them. The walls narrowed. She turned sideways but it became apparent that she could not proceed further.

The whisperers needed her. She needed them. She scraped off the rags of her dress and shoved herself a little further forward.

A crack of light shone down on her from above: the last place, the last test, the last question.

Would she rise to Heaven? Or enter the depths of Hell?

Her flesh split and she shoved herself further into the crack, leaving her humanity behind.

She felt renewed.

Poindexter ate the dress. The flesh, too. He followed the woman deeper and deeper into the place where he had stashed the money. Banknotes…a dragon’s hoard of banknotes.

The stone had been rolled away from his memory. He had stolen the money, not Guillaume. He hadn’t known why he’d done it at the time, only that it was important that he do so. Now he knew. He knew that he’d been used. His sanity, his strength had been stripped away.

The razor was gone but he still had the butterknife, carved into the shape of a small saw.

Goodness would not triumph here. There would be no possibility of justice. Or hope. It was just a matter of what kind of despair would gain a foothold here. You know how this goes as well as I do—the outcome, if not the details. But Poindexter did not.

He thought the knife would answer the thing that possessed the woman, with the condensed horror of all his crimes against humanity. For there to be crimes against humanity, there must be humanity, after all. He would fight for monstrosity, for whispered stories in the dark. He would fight, not for justice, but for the bright spark of fear.

The slitlike cavern widened. He caught up to her as her flickering form reached the bags of money he’d madly insisted on bringing in. The canvas bags could have held grain, or potatoes but instead held…not souls, but something more primitive than that. Starved things, full of want. Mewling growth that, properly fed, could have become men, or monsters, but were instead a kind of blind force, without salvation, damnation, or choice.

He stabbed her with the knife. Shoved it into her midriff, and ground it in deep, twisting it, ripping the blade back, and shoving it in deeper. His hands knew what to do, even though his eyes tried to deceive him, and tell him that the woman was nothing but a ghost.

Blue fire burst out of her flesh and spilled over his hand and up his arm. He screamed in pain. Pain! He had not felt it for a long time, a very long time. But he kept sawing away at her innards.

She turned toward him. It was a motherly face. A loving one. She must have been a good mother, he thought, before the possession had taken her. Limned with blue fire, her face seemed filled with compassion, all-giving, all-providing. She took his wrist and he let go of the knife, his first knife, the one filled with the most savory souls he’d collected, the killers. Every true monster he’d taken was contained in that knife.

It burned with a puff, and she brightened for a moment—then was whole again.

Poindexter knew despair. His human form dissolved like piss running down his leg.

She walked into the first pile of bags, and a ghostly blue fire surrounded both her and the bags, like burning whiskey.

As the starved spirits were consumed, they grew, spreading from pile to pile until all their hoarded treasure was aflame.

Poindexter felt something pulling him from behind, and yielded to darkness.

Karen felt the well of her despair fill, overbrimming, with need. The more she consumed, the less she despaired…but the more she hungered. That’s the way of money, though, isn’t it? Mattie and George were dead, their souls consumed by a different type of monster. That pain remained. The despair—that she hadn’t loved them, that she hadn’t been good enough for them, that she had wanted to die—that was banked fire, however, and she would do anything to keep it from being stirred back to life.

But the money was consumed, all too quickly. She needed more.

Guillaume dragged Poindexter out of the caves by his tail. His clothes, his flesh had sloughed away. His mind had become clearer and more distant, less irrational.

And yet he dragged Poindexter free of the flames before he could be consumed. As the passage narrowed, he rebuilt himself to fit through the available space. It slowed him but not much, and of course Poindexter, with his sinuous, oozing body, could fit through the narrowest of gaps already.

“My souls,” Poindexter moaned. “My knife. My souls.”

They reached the larger cavern. Guillaume ducked as he exited the cave mouth. The horses were gone.

Guillaume rebuilt himself as an engine, like a train but with rolling treads. You wouldn’t have recognized him, but he was a kind of tank, carrying what looked like a thick rope of London fog, only with claws and teeth—Poindexter’s true form. They trundled off along the prairie.

It wasn’t as though the two of them had invented money. Or that it had never before possessed a soul. But they were there, at the turning point.

At a turning point.

Guillaume stopped at a stream to drink, crossed it, and rolled away, puffing steam.

She catches them out on the gray prairie, in a place so remote that their bodies will not be found for generations, and will be mistaken for something other than corpses when they are.

She descends out of the air like glowing blue smoke. Guillaume rolls faster but becomes stuck in wire—barbed wire. No matter how he changes he cannot seem to get it off him. The wire is already one of her servants, and will not release him.

“Go!” he orders Poindexter, and turns to fight her to the last.

Poindexter, now rested, bursts into the air but makes the mistake of looking back. Guillaume is frozen, wrapped in wire but no longer struggling against it. His metallic body softens and changes, not to flesh but to a kind of waxy material, clothed in a cheap gray suit with a bowler hat, the kind of thing Poindexter wears but ineffably different.

Then the thing turns its attention to Poindexter, and he falls from the sky, stumbling on stiff shoes that are supposed to look like leather but aren’t, and that already pinch his feet. The thing’s gaze beats down on his back. He can barely crawl but drags himself toward Guillaume

His flesh is hardening, stiffening. At first hot and flexible, now it’s cooling into immobility. He collapses next to Guillaume. His bowler hat remains firmly affixed to his head.

The two men are indistinguishable now, but for Guillaume lying on his back, and Poindexter on his stomach.

The thing over them turns Poindexter over and straightens Guillaume’s limbs. Now they are indistinguishable. Replaceable, interchangeable.

She sips their souls, absorbing their longing and changing it to the dull buzz of dissatisfaction. They are large souls, old and rich, but she’s able to reduce them to simpler stuff, more easily digested.

Their faces melt a little in the sun, but that’s all right. The flies buzz futilely around them. It would be up to the sun and the wind to erode them: but they would be safely buried in the soil before they had been worn away, and only exposed generations later, when a backhoe went to dig out part of a hillside for a landfill and discovered the plastic manikins already buried there.

Karen turns East.

Flesh, Soul, Money

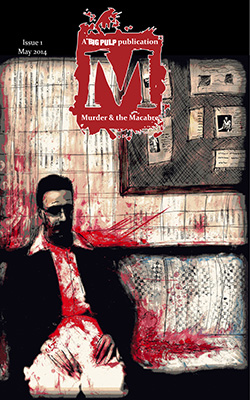

originally published in Way Out West

DeAnna Knippling grew up on the Great Plains, a land driven by expansionism, murder, corruption, and just plain good folks. She lives in a time where souls are bought and sold without even the benefit of a piece of paper to mark the exchange. And she’d feel bad for some of the monsters crushed by such things, but they shouldn’t have been there in the first place. She lives in Colorado with her husband and daughter, has been published in Big Pulp, Black Static, Crossed Genres, and more. Her latest book is Alice’s Adventures in Underland: The Queen of Stilled Hearts. You can find her at WonderlandPress.com and Facebook.